The Lesser-Known Communal Bath: Royal Bath

By Ermeen K.

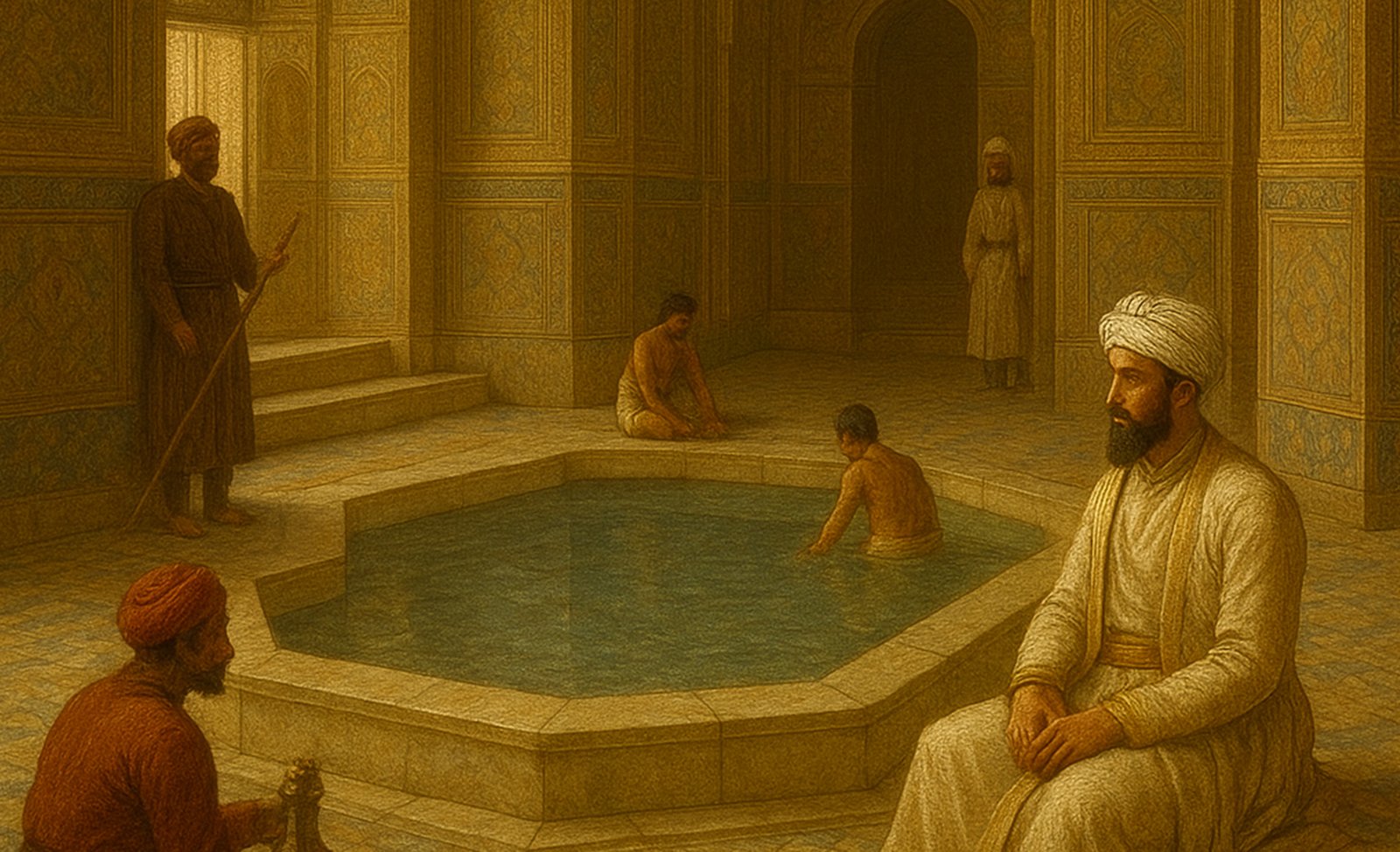

[The image is AI generated]

From ancient times, monumental architecture has served as a powerful instrument for showing power, exhibiting wealth, and immortalizing the cultural significance of a civilization. The Mughal Empire (16th to mid-18th century) developed the grandeur of Indo-Islamic architecture on an unprecedented scale, particularly across the northern Indian subcontinent, encompassing cities such as Delhi, Agra, and Lahore. The Mughals commissioned architectural masterpieces as enduring symbols of their dominance and legacy, signifying both power and spiritual devotion until the decline of their rule.

The Mughals were prolific patrons of architecture, constructing forts, mosques, intricately designed mausoleums, meticulous gardens, and entire cities. This architectural tradition commenced under Emperor Akbar, who exhibited a profound enthusiasm for construction and urban planning. His structures integrated elements of Hindu and Persian styles, marked by the extensive use of red sandstone, adorned with white marble inlays, and elaborate painted ornamentation on ceilings and walls.

Akbar’s son, Shah Jahan, later distinguished himself as a master of architectural marvels, with an eye for proportion, harmony, and stylistic innovation. His reign marked a significant shift in Indian architecture. Introducing white marble as seen in the Taj Mahal, he amalgamated diverse cultural influences—Persian, Turkish, Iranian, Central Asian, and Hindu Indian—into a new architectural era within the Islamic tradition. His contributions represent a pinnacle of Mughal design, characterized by refinement and elegance. Unlike his ancestors, Shah Jahan emphasized simplicity over monumental scale.

One of the lesser-known yet architecturally significant structures of his reign is the Shahi Hammam—a public bathhouse influenced by Persian and Turkish traditions. Constructed in 1635 under the supervision of Wazir Shaikh Ilm-ud-Din Ansari, this hammam is located near the Delhi Gate, adjacent to the Wazir Khan Mosque, and is accompanied by a vibrant spice bazaar. The Shahi Hammam served as a communal space for cleansing and social interaction and has since been repurposed as a boys’ school, a vocational school for girls, a dispensary, and government offices.

Despite having no explicit religious function, the hammam played a role in ritual purification and bodily cleanliness, embodying Turkish and Persian bathing customs. It is exceedingly rare to encounter a structure so richly adorned with frescoes, the Wazir Khan Mosque being an exception. The Shahi Hammam functioned as a sanctuary for travelers to cleanse and rest—a testament to Mughal hospitality and religious affiliation. Water was channeled through a wheel and distributed through gravity-fed systems throughout the hammam. The bathhouse comprises 21 interconnected rooms, showcasing architectural symmetry and decorated with intricate frescoes in Persian and Turkish styles, featuring angels, animals, birds, floral motifs, and geometric patterns. The entrance is towards the west, with the main cold bath in the north adorned by muqarnas and illuminated through carefully designed light wells.

Though evidence suggests the original structure was larger than the present one, much of it was destroyed during Sikh rule. This single-storey building, unlike many Mughal architectural marvels, does not have minarets and grand domes, yet still incorporates white marble, preserving its understated elegance.

The serenity that pervades the Shahi Hammam, even amidst the bustling bazaar of modern Lahore, speaks to its timeless allure. While Shah Jahan often incorporated hammams within private quarters—spaces typically closed to public access—Lahore still has several remnants of communal baths.

August 25, 2025